Sergio Corbucci’s take on the Yojimbo story pits the titular character in between racist Southerners and revolutionist Mexicans, but even for those familiar with the set-up it contains surprising twists and a suspenseful final showdown.

–DB

Sergio Corbucci’s take on the Yojimbo story pits the titular character in between racist Southerners and revolutionist Mexicans, but even for those familiar with the set-up it contains surprising twists and a suspenseful final showdown.

–DB

Leos Carax’s highly lauded montage of various cinematic references and tropes starts with the basics of early silent actualities and a few more framing devices including an audience in a theatre, before starting off on the meat of the meta with a character who shifts chameleon-like between filmic roles as he’s driven from set to set, location to location, occasionally running into other actors who may or may not be placed for another mini-narrative.

It does not take long to get into the flow of the exercise being played with here. When the character of Mr. Oscar switches faces, you get a hint of the new scene about to be played, and then when the scene is actually performed, it’s usually humorously subversive of many major tropes (basically, when you expect a woman to go nude, you end up with something else; when you expect a serious drama about old friends, you get a musical). Unfortunately like most metanarratives there are these moments where one has to really question if an already unpopular trope like the endless death scene is any more palatable when you watch it as a scene about the performance of an endless death scene. Also, Carax throws in some typical meta curveballs with a few sequences placed to make you question whether you are watching just another scene being shot, such as the ‘car accident’ and the ‘midnight laugh.’ We do get some sort of placement into the logic of this metaverse via the driver (who may also be a character actor) and a conversation with a producer that reveals the overall story to be set in a future universe where cameras have gotten so small they’ve become invisible, and actors are carted appointment to appointment rather than sticking through sustained feature length movies.

Thus, underlying the theme of this exercise is exhaustion, exhaustion of the common cinematic tropes and exhaustion of a depleting actor base as the audience become less and less interested in ‘the cinema’ and consumer cameras become smaller and taken more for granted. A continuitous dream sequence (because there’s a dream sequence within one of the shoots Mr. Oscar attends) is performed by the use of datamoshing, a technique where video encoding is altered to create surreal morphological shifting between frozen pixels to draw attention to the brittleness of the current cinematic apparatus, digital video.

If only modern movies were more comfortable at going to the level of surreality as someone like Jean Cocteau, one of the many visual references this movie employs, without requiring some establishment in a logical, somewhat science fiction future framework. Also, once the movie-within-a-movie picaresque is established, it’s not really necessary to commit to any one sequence or line of dialog to find deeper meaning or significance. This is one of those movies that’s not difficult to understand if you’ve seen more than a few non-Hollywood movies, whereas people who’ve never stepped far outside a genre movie diet will love to hate it and exaggerate its ‘randomness’.

–Dane Benko

Cloud Atlas more tightly interweaves the six narratives from its source along rising and falling action instead of a relatively flat 1 2 3 4 5 6 5 4 3 2 1, but the protraction of each beat to repeat over matching actions can still make it feel topheavy. The fact that the three directors held the whole production together and the editing flows smoothly is admirable regardless.

–DB

This movie makes me want to read Kaufman’s scripts themselves to see how they describe action in such a way that all directors, even a relatively non-stylistic one like Clooney, manage to fall right into his surreal layers-of-cardboard-backdrop world. This movie is not nearly so ‘meta’ as Adaptation. or Synecdoche NY, yet visually questions Barris’ memoirs as a kitsch fabrication similar to the shows he produced.

–DB

Begotten (1990)

This experimental feature has gained some cult status from reuse of its imagery in Shadow of the Vampire and Marylin Manson videos. Unfortunately it’s one of those ‘films’ that should be seen on film, as the optical-printer post-production effects are based on the emulsion medium itself. Anyway, think a visceral and gory Kenneth Anger: Merhige is a religious relationship to cinema and this is his genesis story.

Shadow of the Vampire (2000)

This movie is one of those loving homages that feels like Merhige wants to own the original as his own child; nevertheless the casting wins it over with Malkovich portraying Murnau as a sacrificial high priest of cinema and Defoe as an antsy, irritated aging vampire both camera shy and obsessed with the lead actress. It’s not a very chilling movie but quietly crazy.

Suspect Zero (2004)

The script obviously was written to ride off of Se7en’s audience, but Merhige can’t help taking the paranormal investigator aspect seriously; playing off of the popular conspiracy theory about psychic CIA operatives, the movie extends it to the FBI. Merhige elevates the script with some interesting headache and psychic input abstract montages but not much saves this generic thriller from itself.

Final Word: Merhige believes cinema replaces literature and has a deep but dark spiritual affiliation with it, which results in interesting imagery and quietly mad narratives but doesn’t give him much room to play in the mainstream and doesn’t always pan out to a novel elevation of the form.

–DB

Uh. Zuwalski gives you .2 seconds to adjust and then it’s direct to the howling fantods as characters claw, yell, cry, and seizure their way through a narrative featuring jealous infidelity, doppelgangers, conspiracy, religious anxiety, petty hatreds, possibly the birth of the antichrist, definitely the end of the world, and a gag-inducing tentacled sex monster. Other than that it’s really, really weird.

–DB

Somewhat typical Euro-trash horror intercuts the roving monster stumbling upon scenes of nudity with one woman’s plan to justify her father’s creation… by suturing her lover’s brain into a hunky new body. The script at the heart of this thing is surprisingly vibrant, meaning if the movie was aiming for some other type of production value we might have had a real, instead of an ironic, cult classic.

–DB

I’ve always loved Wes Anderson but none of his films have replaced Royal Tenenbaums as my favorite until now. Here he mixes his pastel expressionism with abjectly real moments from preteen memory, making his calculated awkwardness actually awkward and his cheery quirkiness actually cheerful. Oddly enough, this adventure movie becomes surrealism at some moments and even feels like Anderson’s homage to Hammer Horror.

–DB

The Scary Movies were redundant because Scream was already funny. In Scream 4, Craven updates the series to match new trends while keeping true to the series and making sure the movie is still actually good — like Shaun of the Dead, which he references at one point. Very creative use of cellphones and webcams without turning into a found footage piece. The only problem is the dragged out multiple openings.

–DB

One of George Lucas’ statements surrounding the sale of LucasFilm LTD. to Disney is that he will be making “experimental movies.” Now if you think about the differences between anything from the early Edison experiments to some people calling Cloud Atlas experimental because it balances six traditional narratives simultaneously instead of focusing on one, the term experimental has never really been definitive in the history of cinema. So what could he mean? After all, his breadth is not confined to adventures through space and Christian (alien?) iconography, as he’s had a hand in producing anything from Godfrey Reggio’s Powaqqatsi to Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha.

Well, if we look back to some of his early short films, they may just provide some hints toward the type of stuff Lucas may be gearing down to do.

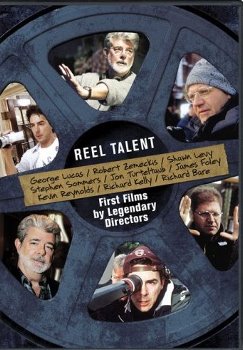

A DVD collection called Reel Talent features student films created by Lucas during his time at USC. Below are reviews of two of his films from this set.

1:42.08 to Qualify (1966)

This seven minute long short is relatively light on narrative. It protracts a lap made by driver Peter Brock in a 1100cc G Modified Lotus 23 to qualify for a race. Lucas uses the opportunity to explore different ways of shooting and editing the vehicle, from close-ups showcasing the internal mechanisms of the Lotus 23 to abruptly different angles to showcase its course and try to create differing illusions of speed and acceleration. Near the end a plot point is placed into the otherwise abstract technical experiment as the car drifts and then control is reclaimed.

This short is, perhaps, not going to be very interesting to the type of audiences eager to see Star Wars mythic narratives, but other students and filmmakers can appreciate the techniques and how Lucas seems to be learning how to shoot and edit in real time just as a racecar driver is figuring out his controls. A sort of unintentional allegory can be read here about starting off on your own lonely track and managing to qualify for the big race. Or George Lucas just really likes cars, since he wanted to be a racecar driver and went on to make American Graffiti.

Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB (1967)

Along with Freiheit, this movie is sort of a prototype of THX 1138, itself justifiably ‘experimental’ in terms of minimalist mise-en-scene (like a futuristic A Man Escaped, really). Here is where I play with fire critically and state that Electronic Labyrinth is far more interesting than the feature length sci-fi classic that shares its name, mostly because it’s more maddening.

A chaotic, fractured race occurs resembling the closing escape from THX, only built out of substantially cheaper ‘sets’ (that are more like found locations). To match the dissonant visuals are equally dissonant sounds, as electronic voices and computer noises seem to ‘track’ the runner through the ‘electronic labyrinth’. At any given point it is unclear precisely what is happening, which is why most viewers are likely to write off this film on principle. In another sense, the experience is absolutely what I imagine trying to escape a virtual reality after your mind has been uploaded and a virus has taken over would be like. It is a rather psychedelic and visceral project, effects that are disappointingly missing in Lucas’ more massive and mainstream work.

These two movies point the way toward a tech geek keenly interested in developing every level of production and expanding upon different methods of using those techniques. For someone more interested in experimental film, it makes his later career more disappointing than the Star Wars prequels were to many fans. It would be nice to see Old George Lucas dig up Young George Lucas and tinker around like he used to, but it’s really hard to tell what he means based off of what he says anymore.

–Dane Benko